DOB/DOD: December 9, 1895 (Thomaston, CT) – December 7, 1941; 45 years old

MARITAL STATUS: Unmarried

LOCAL ADDRESS: 31 Goodwin Court, Thomaston

ENLISTMENT: July 20, 1917

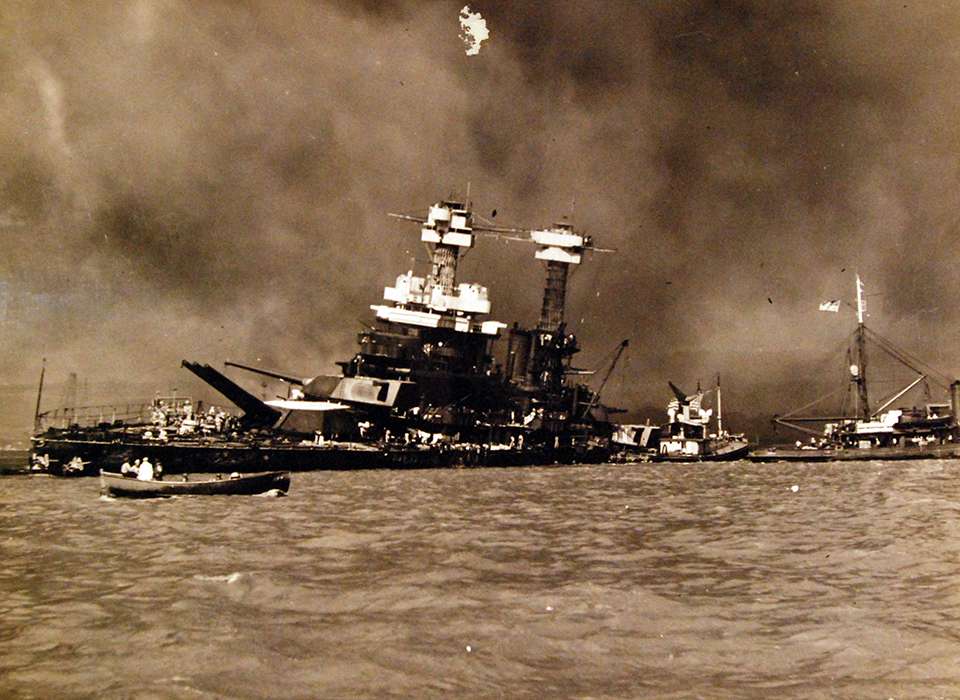

SHIP ASSIGNED TO: USS California (BB-44)

FAMILY: Born to William Reeves (1850-1938) and Mary O’Riley Reeves (1858-1939), both born in Ireland. One sister, Rosetta Reeves (1882-1905). Four brothers, Joseph (1885-1972), Leo (1889-1967), William (1892-1949), and Frederick (1898-1970).

CIRCUMSTANCES: He enlisted in the Naval Reserve as an Electrician Third Class on July 20, 1917 and was discharged on August 21, 1921. Less than two months later, on October 12, 1921, he reenlisted in the Navy, making it his career. He was serving as Chief Radioman on the battleship USS California when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

From U.S. Navy cruise book published in 1995 about the USS California

THOMAS JAMES REEVES, the son of Mr. and Mrs. William Reeves of Thomaston, Connecticut. He attended local schools and, before entering the service, was the chief operator for Western Union at Waterbury, CT. Thomas enlisted in the U.S. Navy on July 10, 1917. He saw service in WWI in the Transportation Service. In the following years, he served on the USS American, Whipple, Seattle, Texas, Chicago, Maryland, New Mexico, and California. He also served in the Staff Headquarters of the 3rd Naval District and with the Naval Mission to Brazil. He also taught radio in Rio de Janeiro. Thomas intended to retire in 1939, with more than 22 years of service completed. He had accepted an appointment as a ground engineer with the Civil Service. The day before his retirement was to take effect, President Roosevelt declared a Limited Emergency, and all persons were prohibited from leaving the Navy. Thomas then re-enlisted at San Pedro for another four years. At the time of Pearl Harbor, he was on the Admiral’s staff on board the USS California.

A remembrance letter written by Thomas Mason. On display at the Town Hall in Thomaston, Connecticut

A remembrance of Chief Radioman Thomas J. Reeves, Medal of Honor

One day in the summer of 1941, Chief Reeves called me over to the supervisor’s desk in the radio room of the battleship California. We were moored to Berth F-3 at the head of the battle line in Pearl Harbor.

“Mason, I’m giving you a promotion,” he said. “I’m sending you to the main top for your battle station.”

“That’s great, chief!” I enthused. “What do I do there?”

“When our planes are up, you copy their spotting reports,” he said. “By hand. They’re used for correcting main-battery fire.”

“What do I do when the planes aren’t up?”

“Enjoy the scenery.” He smiled. “You’re going to like it up there, Mason. Lots of fresh air.”

The chief — who ran the 90-man radio gang of both the ship and the admiral’s flag complement with an awesome competence — had given me more than a promotion. He had, it is quite likely, given me my life. Otherwise, I would have been in the main radio, located on the platform deck below the third deck, port side, on December 7 when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. After it flooded and was abandoned following the deadly impact of two torpedoes, I would have been with my best friend, Melvin G. Johnson, near the ship’s service store when a bomb hit there, killing him and about fifty other shipmates. Or — had I been a better man than I probably was — with Chief Reeves in a burning passageway on the third deck.

When the main radio was abandoned, Chief Reeves was the last man out. After helping some men to relative safety, he returned to the burning, rapidly flooding the third deck. Realizing the desperate need for ammunition at the anti-aircraft batteries, he plunged into the smoke and flames with every able-bodied man he could muster. It was there on the starboard side of the third deck, less than fifty feet from the entrance to the radio room he had supervised so long and so ably that he was overcome by smoke and fire, collapsed, and died. He won the nation’s highest award for valor, the Medal of Honor. Of this medal, Harry Truman said: “I would rather have it than be President.”

The last time I saw the chief was on the late evening of December 5, 1941, in front of Wo Fat’s restaurant on Hotel Street in Honolulu.

“He was one of those men of above-medium height and large frame who become corpulent but never look fat,” I later wrote. “He had a round, smooth face under a full head of thick, iron-gray hair that gave him a leonine look despite the military haircut. His piercing, hawk-like eyes could have been those of a surgeon — or a riverboat gambler.

“Even then, he was a near-legendary figure. A pioneer during the primitive days of the arc transmitter, he was a man who scorned the easy shore billet that could have been his for one of the toughest jobs in the enlisted Navy: chief in charge of the radio gang, Commander Battle Force. He ran the C-D Division with a discipline that was firm without being oppressive… Reputedly, he had turned down a commission of at least two stripes, which was certainly understandable, for no junior officer in a battleship had anything like his real authority and prestige. The chief alone decoded when and where you stood watch, what your battle station was when you went on liberty, and when you were ready for a faster radio circuit or an advance in rating. Within his division, he was more feared and respected than the captain himself.”

On this Friday evening of December 5, Johnson and I were nearly broke. Spotting the chief, I ran across the street and explained my problem.

“Well, Mason,” he said without hesitation, “let me make you a small loan.” He pulled the bill from one of his pockets and handed it to me. “That enough?” he asked.

I was holding a twenty dollar bill — a third of a month’s pay for a third-class petty officer. I must have stammered in explaining that I didn’t need so much, that a five would be plenty.

“That’s all right, Mason,” he said with a wave of the hand and a flash from the large diamond ring he wore on his little finger. “Keep it.”

A Japanese task force prevented me from repaying that loan, but I never forgot the obligation. My assignment to the main top by Chief Radioman Thomas J. Reeves of Thomaston, Connecticut, enabled me to survive the attack on Pearl Harbor and later to attend college on the G.I. Bill. Decades later, it made possible the repayment of my debt in a coin of a different kind. When I was asked by the Naval Institute Press to write Battleship Sailor, I was, at last, able to pay tribute to my gallant chief radioman of the California and to include his name in the book’s dedication.

“The battleship Navy was gone as an overwhelming physical force,” I wrote in my memoir, “but I knew that some of its intangible legacies would remain. What would live for others to emulate and for history to admire were the qualities of men like Reeves. To such men, defeat was unendurable; failure was not acceptable.”

I am proud to have known and served with Chief Radioman Thomas J. Reeves, Medal of Honor.

Theodore C. Mason

NOTE: Theodore Charles Mason survived the war and died at 82 years old in 2004.

A letter typed on State of Connecticut letterhead dated June 2, 1942

Mr. Fred Dewey Reeves

31 Goodwin Avenue

Thomaston, Connecticut

Dear Mr. Reeves,

I write this to you with a heart filled with deep sympathy for the family and friends of Tommy Reeves, who died so that we may live. In a brief moment of sublime heroism, at a time when all the laws of Nature and humanity were being violated by a treacherous foe, Tommy Reeves reached out, beyond his duty and beyond his obligations to his fellow men, to make the supreme sacrifice.

That he was the first son of Connecticut to die in battle during this universal war places him high up in the ranks of those other noble souls who, down the years, since the community was first founded, fought and died for freedom’s sake. He has enriched our heritage by becoming part of it.

Words are always inadequate to describe the mingled and profound feelings that the death of such a hero inspires, for nothing that is said or done can ever quite capture that divine spark that was in Tommy Reeves when he went to his death. Of all the acts of heroism, such an act as his is the most heroic. He knew for certain that the task he had assigned himself would be the last of his life on earth. He was not essentially a fighting man but a technician. He was the Chief Radioman on the Battleship California, and when that ship was bombed from the air as it lay at anchor in Pearl Harbor, Thomas J. Reeves helped to keep the guns of his ship blazing at the enemy. Time after time, he carried ammunition up a gas-filled and smoke-filled passageway to the men who manned those guns, and he kept on doing that until the gas and the smoke stopped him. He did not stop at the moment when he could have saved himself, but he continued until it was impossible to do anymore — until he died. Only great and divinely courageous souls are capable of that kind of heroism.

For it, for his immense service above the line of duty, he has been posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest military award that is in the power of our country to bestow. And for it, he has been given that place in the hearts of his countrymen, which is open only for those who rise like a phoenix to give light and hope, and courage to the rest of us. What he did shines as an example and an inspiration to all who love liberty. To his family, his friends and comrades, his neighbors, for whom the mark of honor must seem slight compensation for the death of a loved one, I would say that there is deeper consolation in that what Tommy Reeves did was not done futilely. It will not be said that he died in vain, but rather that he died for all people everywhere in the world whose future, whose hopes, whose spirits were being destroyed by brutal forces. It will be said that he died so that the light of God and the air of freedom would not be suffocated by a world tyranny. It will be said that he died so that the promise of God of a world of peace and goodwill was one day fulfilled. It will be said that he died for all those who will come hereafter, in this blessed land, for the families that will come, for the new communities that will come, for the new cities that will come, for all the homes and the schools that will come and so that all of these could blossom and thrive in the clear light of a wonderful and free democracy.

We are fighting the war to make that vision of the future a reality, and we will not stop fighting until it is a reality. Tommy Reeves poured his strength and his splendid life into that cause. He has had a hand in the making of a new world, and forever after, in whatever there will be of goodness, of decency, and of human happiness, there will be something of Tommy Reeves.

Let us mourn for him, but let us know, as the poet Shelley knew of his friend Keats:

“Till the future dares forget the past

His fate and fame shall be an echo and

a light unto eternity.”

Believe me to be

Sincerely yours,

Robert A. Hurley

Governor

Citation to accompany the award of the Navy Medal of Honor

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Congressional Medal of Honor to Thomas James Reeves, CRM (PA) USN, Deceased

For distinguished conduct in the line of his profession, extraordinary courage, and disregard of his own safety during the attack on the Fleet in Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces on 7 December 1941. After the mechanized ammunition hoists were put out of action on the U.S.S. California, Reeves, on his own initiative, in a burning passageway, assisted in the maintenance of an ammunition supply by hand to the antiaircraft guns until he was overcome by smoke and fire, which resulted in his death.

Photo of CRM Reeves’ Medal of Honor on permanent display in the Town Hall in Thomaston, Connecticut. Photo by the webmaster.

From The Hartford Courant July 12, 1942

Thomaston, July 11. – (AP) – Thomas Reeves is to have a United States Navy escort vessel named in his memory, according to a letter received today by his brother, Fred D. Reeves, from the Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox. Mr. Reeves, whose memory was honored at special ceremonies here on May 30 and who was posthumously awarded the Navy Medal of Honor, died December 7 in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He was a Chief Radioman in the Navy. The first Reeves was laid down by the Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Virginia, on 7 February 1943; launched on 23 April 1943; sponsored by Miss Mary Anne Reeves, niece of Chief Radioman Reeves; and commissioned on 9 June 1943, Lieutenant Commander Mathias S. Clark in command.

USS Reeves (DE-156/APD-52) was a Buckley-class destroyer escort of the United States Navy, named in honor of Chief Petty Officer Thomas J. Reeves (1895–1941), who was killed in action while serving aboard the battleship California (BB-44) during the attack on Pearl Harbor. For his distinguished conduct to bring ammunition to anti-aircraft guns, he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

The first Reeves was laid down by the Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Virginia, on 7 February 1943; launched on 23 April 1943; sponsored by Miss Mary Anne Reeves, niece of Chief Radioman Reeves; and commissioned on 9 June 1943, Lieutenant Commander Mathias S. Clark in command.

Chief Reeves is buried at the National Military Cemetery of the Pacific, 2177 Puowaina Drive, Honolulu, Hawaii; Section A, Grave 884. Photo from FindAGrave.com.

Also memorialized on his parent’s headstone. The stone is located in St. Thomas Cemetery, 55 Altair Avenue, Thomaston, Connecticut; Section B, Plot 283. Photo by the webmaster.

END

Discover more from Honor Norwalk CT veterans

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.