DOB/DOD: June 7, 1916 (Norwalk, CT) – March 17, 1992 (Norwalk, CT); 75 years old

MARITAL STATUS: Martha E. Blackman (1918-2000) on October 29, 1948, in Stamford, CT.

CHILDREN: Jack Arthur Werner (1952-2014).

LOCAL ADDRESS: Strawberry Hill Avenue and 90 Newtown Avenue, Norwalk

ENLISTED: August 21, 1941 (before Pearl Harbor)

SERVICE NUMBER: 31049856

DISCHARGE: November 5, 1945

UNIT: 91st Bombardment Squadron, 27th Bombardment Group

FAMILY: Born to William C. [born in Germany] (1890-1958) and Marie M. Loeffler Werner (1895-1956). One sister, Mary A. Werner Sisko (1927-1981).

OTHER: Past Commander of VFW Post 603 in Norwalk. Also past Commander of the Disabled American Veterans Post 26. Member of the Purple Heart Association, Trench Rats #42, and American Legion Post 12.

OTHER 2: The first person from Norwalk who was wounded in World War II.

From The Norwalk Hour December 27, 1941

LOCAL BOY HURT IN PHILIPPINES

PARENTS OF PRIVATE ARTHUR E. WERNER OF MAIN STREET GET REPORT; BELIEVED INJURED IN JAP RAID

Private Arthur W. Werner, son of Mr. and Mrs. William Werner of 142 Main Street, was seriously injured on December 7 in action in the Philippines; his parents have been notified in a telegram from the U.S. War Department. The telegram received here on December 24 did not disclose the nature of Private Werner’s injuries nor where he had been located. He is an airplane mechanic, however, and it is thought likely here that he sustained his injuries during a raid on a U.S. air base. Private Werner is a graduate of Center Junior High School and Norwalk High School and is about 22 years of age. He was employed at the Stamford Rolling Mill before enlisting in the U.S. Army six months ago. The report of serious injury to Private Werner is the first report received here of injury to a local lad in service. Mr. and Mrs. Werner are seeking further information from the War Department.

From The Norwalk Hour June 8, 1942

MAIN STREET YOUTH, INJURED, TELLS STORY OF FIGHT IN PHILIPPINES

Arthur Werner, Home on Short Leave, Was Hit By Jap Shrapnel In Stomach And Leg; 3 of Pals Wounded Too; Taken To Australia Hospital Then Home To Fort Dix

Still carrying on his body the marks made by shrapnel from Japanese bombs, Private Arthur W. Werner, son of Mr. and Mrs. William Werner of 142 Main Street, was back home from the Pacific over the weekend after a military odyssey that took him halfway around the world and back and now has him facing nine months of convalescence before he can do what he most desires — “go back and get the boys I left on Bataan.” A modest youth who received his serious injuries a week after the war began when a Japanese bomb exploded 35 yards away from where he and seven other aerial gunners crouched near Nichols Field not far from Manila. Werner is now stationed at Fort Dix, N.J., completing a convalescence that began in a hospital in the bomb-ridden Philippine capital, continued on a hospital ship as it steered its perilous course southward to Australia, and extended further in a hospital in a big city in the land down under. Werner is back at Dix today but he expects soon to get a long furlough, which he will spend here with his parents and his sister, Mary Ann. He he still on crutches, which he expects to use for another nine months, but he looks forward to the time when he can again go into action. Before he enlisted in the Army in August of last year, Werner had attended Roosevelt, Center, and Benjamin Franklin Schools here, other schools in Newark and Brooklyn, the Roosevelt Aviation School on Long Island, and he had worked in the Yankee Metal, Norwalk Tire, Streb Fur and other plants in this city and the Stamford Rolling Mills. Werner enlisted in the Air Corps on August 24. He spent three weeks at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, went to Savannah, Georgia, for two weeks more, and started for the Pacific, crossing the country by train and sailing in front of San Francisco. Little time was wasted in crossing the ocean. Werner stopped just seven hours at Hawaii on the way and landed at Manila on November 20 — 17 days before the Nipponese treachery was to burst on the world.With others, Werner was given a concentrated course of training in aerial gunnery — a skill he has not yet had an opportunity to use, as he received his disabling injuries while waiting for an opportunity to go aloft to “get ‘em.” On Sunday, December 1, Werner told an Hour reporter that General MacArthur — who holds the same high position in the minds of the men under him as he does in the minds of those of us at home — ordered all his forces to be on a 24-hour alert. On the morning of December 8 — which was the same day as December 7 here — word of the attack on Pearl Harbor was received, and all the Philippine forces braced themselves for the attack they knew was coming. Werner’s bombardment squadron was ordered to disperse its planes in a banana orchard, the men of the squadron taking up stations in foxholes and slit trenches nearby. They were about three miles from Nichols Field. At about 1:30 A.M. on December 9, Werner, sleeping in a tent, felt the ground shaking and heard thunderous noises, which let him know that an attack had begun on their base. Werner has a penciled diary on which he has listed the events of the days that followed. The entries read almost alike, telling of the number of raids, which appeared to be staged by the Japanese regularly, three times a day, at the regular meal times. One entry reads: “December 10 — Cavite bombed. Corregidor hits back.” On the 12th, a call came for volunteers to go to relieve the personnel at Nichols Field, which had been depleted by casualties, and Werner was one of the eight volunteers selected from his squadron. “They would all have gone, for that matter,” he said. The volunteers moved up to the field and were dispersed a short distance away from it, awaiting an opportunity to take off. “We were lying on the flat back of a creek across a road from the field about mid-day on the 13th,” Werner said, “when somebody yelled, ‘Here they come!’ “We all flattened out and watched 15 big Jap bombers go overhead, dropping bombs all over the place. They were flying too high for our anti-aircraft to get them. Then more of them came, 64 in all, I think, and they made three runs over the target, coming closer each time. “A big bomb exploded about 35 yards away from where we were lying. It got four of the eight boys from my squadron.” Werner himself was injured about the right leg and in the stomach by shrapnel from the bursting bomb. Much of the shrapnel is still in his body today. The Norwalk soldier was taken by truck, after the raid, to Fort McKinley, where he was given first aid. Put under ether, he awakened later in a hospital in Manila itself. “When I came to, another raid was going on.” he said. There were dozens of raids on Manila during the time Werner was hospitalized there, unable to seek any protection. Bed patients who could move, he said, simply clambered under their beds when the raids started, but others like himself could merely lie in bed. “We were never left atone,’ though,” he said, “because the nurses and the doctors kept right on with their work.” As it happened, the hospital was never bombed, although nearly everything else in Manila, which General MacArthur had declared an open city, was. “The Japs would fly over the city for a half-hour, lining everything up and taking aim and then let go with their bombs. There was no opposition, as all the anti-aircraft had been moved out of the city.” Werner spent Christmas Day in the hospital. The Red Cross gave him and the other wounded soldiers toilet kits, and a group of carolers strolled through the ward, singing the Christmas hymns. “And believe me, they sounded better than ever,”” Werner said. On Dec. 31, Werner and 240 other wounded soldiers were put aboard the S.S. Mactan, a small hospital ship, which headed for Australia. As the New Year came in, a few hours later, the tiny boat was passing Corregidor. “We could look back and see Manila burning.” Werner said, “I don’t know what it looked like when Rome burned, but it must have looked something like that. There was fire and a red glow and clouds of smoke everywhere. And we knew the suffering that went with it.” The tiny ship sailed south to the Netherlands East Indies and, after a stop of a few days, went further south to the — northern part of Australia. Taking aboard oil and supplies, it started down the coast for a city in the southern part; the ship’s engine room caught fire, burning for an hour. “Incidentally,” Werner said, “during the fire and for hours

afterward, we didn’t sight a single ship or a single plane, but that night, the Japanese news broadcast told about the fire on board, claiming to have bombed us. They hadn’t bombed us, but how they knew about that fire, I’ll leave to your imagination.” The trip to the southern port was almost over when a young Filipino soldier, badly wounded and despondent over what had happened to his country, jumped overboard and drowned. On January 27, almost a month after they had stolen out of the darkness of Manila Bay, the wounded soldiers arrived at their Australian destination, being taken at once to a hospital. For Werner, the days that followed were long ones, as he was confined to his bed. They were livened, however, by the visits of an Australian girl whose name, if the glances the Hour reporter stole at the soldier’s diary, hit the right spot, is Marle. On February 28, Werner had his first leave from the hospital, being allowed to go into town for the day. On April 19, he sailed for the United States, arriving here on May 22. Three days later, he was at Fort Dix, and after a ten-day waiting period, he was granted a three-day leave, coming immediately to his home in this city. The reunion at the Werner home that followed on Friday was a memorable one. On Saturday, Werner was driven around town by friends, calling on acquaintances. He is now back at Dix, awaiting his long furlough. While in Australia, Werner broadcast greetings to his home, a record of the broadcast, turned over to the Norwalk Hour by station WOR, having been presented to his parents. Werner’s many friends here are glad to see that he is recovering from his serious injuries. His attitude, despite the hardships he has endured, is all that any morale officer could want it to be. When an Hour reporter mentioned this to him, he said: “Look, I don’t know how you’re going to write this up, but don’t make me out a hero. I only lasted there for a week, but my buddies fought it out on Bataan and on Corregidor for weeks. Put it in the paper that they’re real heroes because they are, and I only wish I had been able to be in there with them at the finish.” “Do you expect to see them again?” he was asked. “You bet I do,” he replied. “Because we’re going back there to get them.”

From The Norwalk Hour June 19, 1980

It was New Year’s Eve 1941 when an aged inter-island steamer churned out of Manila Bay in the Philippines, carrying 224 injured Americans away from the clutches of the approaching enemy. Behind the ship was the city of Manila, engulfed in flames as the invading Japanese army swarmed in. Ahead lay an incredible 5,000-mile journey through enemy waters in a boat considered unseaworthy for travel on the high seas. Arthur Werner, of 90 Newtown Ave., Norwalk, was a 27-year-old U.S. Army soldier aboard the freighter ‘‘Mactan” that evening. “I remember thinking, ‘This must be what Rome looked like when it burned,’’’ reflected Werner recently. The use of the ‘‘Mactan’’ as a hospital ship was a desperate attempt by the U.S. Forces under Gen. Douglas MacArthur to move the seriously wounded from Manila. Few realized at the time that the internationally sanctioned Red Cross effort would make the ‘Mactan’ the first U.S. Hospital ship of World War II. This event is the topic of a recently published book titled, ‘Mactan: Ship of Destiny,’’ by William L. Noyer. In it, the survivors of the voyage, ‘the Patients, crew, and staff, recount their adventure. The events leading up to the voyage of the Mactan began on Christmas Eve 1941. On that day, just two weeks removed from the tragic events of Pearl Harbor, Gen. MacArthur elected to withdraw his troops from Manila to Bataan. The 224 seriously wounded patients in the hospital in Manila had to be left behind to await certain capture by the Japanese Army. In the days that followed the retreat of the American Army, U.S. Officials working with the American and Philippine Red Cross tried frantically to find a way to remove the patients from the port city. After much searching, the S.S. Mactan, a 300-foot, two-masted, oil-fired steamer built in 1899, was located. The ship reflected one crew member, ‘‘was not much bigger than a Staten Island ferry,’’ and few people believed it would survive the journey that lay ahead. All it was being used for at the time was hauling munitions around the islands. Werner joined the Army in August 1941. After joining the Army Air Corps and after three months of being stationed in the United States, Werner arrived in the Philippines on November 20, 1941, a little more than two weeks before the start of World War II. On Dec. 13, he was seriously wounded in a bombing raid on Nichols Air Field, an incident that would lead him to be on the voyage of the Mactan.” Pretty shocking,’’ said Werner, reflecting on his feelings when he heard of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. ‘‘We had turned all our equipment in at Savannah (Georgia) Air Force Base, we were supposed to get all new stuff there (Philippines). When it broke out, we didn’t have any aircraft. to work with so -we became foot soldiers.”’ Werner remembers Manila as a boarded-up city expecting to be overrun. The sounds of gunfire and explosions were constant reminders that the war was only miles away as he lay in his bed in Sternberg General Hospital in Manila. The Mactan, once located, had to be readied for its mission as a Red Cross ship. It had to be painted white with giant red crosses painted in various locations, which it was hoped would ensure the ship’s safe passage. Also, the entire cargo of guns and ammunition had to be dumped overboard. Despite the preparation, conditions on board were miserable, and there were strong fears that the boat would break up in the first ocean storm. “They claim the boat was so old…I don’t know…It did the job, I tell you that.’’ recalls Werner. Remarkably, the Mactan was not attacked, though its position was monitored by Japanese radio. The worst incident occurred the evening of January 15, about two weeks after the ship set sail, when a fire broke out in the engine room. The men prepared to abandon ship into the shark-infested waters, but quick work by the crew saved the ship and averted certain disaster. The ship plugged on and, after stops in Darwin, Townsville, and Brisbane, Australia, arrived in Sydney, Australia, on January 27. The wounded and crew were given a hero’s welcome. Werner, who had the unenviable distinction of being the first Norwalk resident injured during World War II, was laid up with his wounds for 10 months. He stayed in the service, however, serving in basic training in Atlantic City, pilot training school in Denver, and the Air Force test proving grounds in Florida doing aerial photography work until his discharge in November 1945. He was not allowed to return to active duty. Since leaving the service, Werner has been active in the Disabled American Veterans organization, having been treasurer of the local group for the past 10 years, and he has been active in the Veterans of Foreign Wars. He is a past commander. Altogether, all but 27 of the 224 patients, plus staff and crew remain alive. The sad ending belongs to the Mactan itself. “The last anybody saw of it was in 1950,” said Werner sadly. ‘‘It was seen heading out of Manila Bay, out to sea. It was heading to Hong Kong to be sold as scrap metal,’’ he said, showing the hurt one would feel when thinking of a long-lost love.

From The Norwalk Hour March 18, 1992

ARTHUR W. WERNER

Retired plumber, active in veterans’ groups

NORWALK — Arthur W. Werner of Newtown Avenue died Tuesday at home. He was the husband of Amelia Eula Werner. Born in Norwalk on June 7, 1916, Mr. Werner, son of the late William and Marie Loeffler Werner, was a lifelong area resident. Mr. Werner was a retired plumber with John A. Campbell Plumbing and Heating Corp. A U.S. Army Air Corps veteran of World War II, where he served as a sergeant, Mr. Werner was a past commander and treasurer of the D.A.V. No. 26 and past commander of the V.F.W. Post No. 603. He was a member of the Purple Heart Association, Trench Rats No. 42 and the Frank C. Godfrey Post No. 12 American Legion. Mr. Werner had been a two-time grand marshal in the Veteran’s Day Parade. In addition to his wife, Mr. Werner is survived by several nieces and nephews. Services will be held at 11 a.m. Thursday in Collins Funeral Home, 92 East Ave., with the Rev. Russell B. Greene Jr., pastor of the Lutheran Church of the Good Shepherd, officiating. Interment with military honors will take place in Riverside Cemetery. Friends may call from 9:30 to 11 a.m. Thursday at the funeral home. The V.F.W. Post No. 603 will hold a service at 10 a.m. Thursday in the funeral home. The family requests that contributions be made to Mid-Fairfield Hospice, 31 Stevens St., Norwalk 06850.

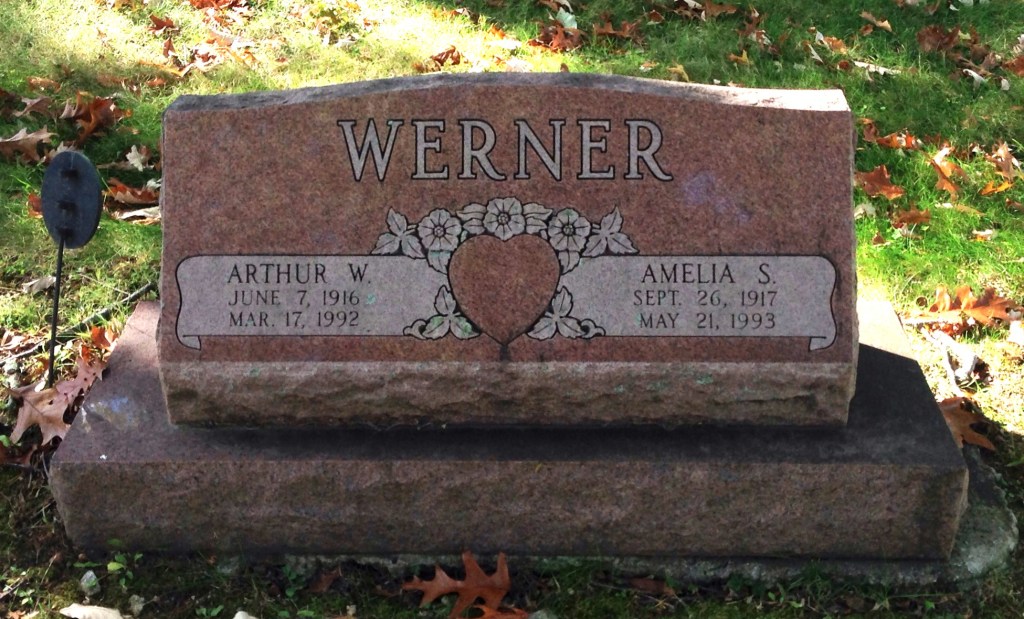

Buried in Riverside Cemetery, 81 Riverside Avenue, Norwalk, Connecticut; Section 17.

END

Discover more from Honor Norwalk CT veterans

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.